Fauré: inventing musical forms

by Jessica Duchen*

![]() Listen to show |

Listen to show | ![]() View complete program

View complete program

RealAudio; (How to Listen)

|

|

|

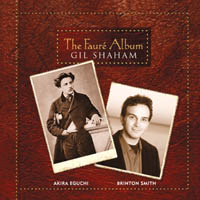

Gil Shaham—The Fauré Album

|

'Fauré's achievement was to invent musical forms which attracted our hearts and senses without debasing them. He offered an homage to Beauty in which there was not only faith, but a discreet yet irresistible passion…The delicate precision of his architecture, the concision (without dryness) of his ideas will long guide us in our moments of anxiety.' So wrote the composer Georges Auric in tribute to the subtle genius of Gabriel Fauré, a musician who had risen slowly from a modest background to become arguably the founding father of French music in the 20th century.

Born in 1845 near Pamiers in rural south-west France, Fauré was the youngest son of a schoolmaster's large family. His musical inclination showed itself early; when he was only nine years old his father was recommended to send him to the Niedermeyer School in Paris, which specialised in the training of church musicians. Here the somewhat dreamy, unambitious and homesick little Gabriel might have grown up to be solely a church organist and choirmaster "“ jobs he did hold for much of his adult life at the prestigious Madeleine in Paris. But among his teachers was the dynamic young Camille Saint-Saëns, who galvanised him into trying his hand at composition. Convinced of his pupil's gifts, Saint-Saëns took Fauré under his wing; he remained Fauré's closest friend and champion for the rest of their long lives.

It was through the well-connected Saint-Saëns that Fauré "“ by then working as a church organist while composing his early songs and instrumental pieces "“ came to know Pauline Viardot and her family. Viardot had been the greatest mezzo-soprano of her day, acquainted with many of the artistic luminaries of the 19th century, not least Chopin and George Sand. She had married the theatre director Louis Viardot in 1840, but when she performed in St Petersburg the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev fell in love with her and followed her back to Paris. Turgenev subsequently spent most of his life in her household; her four children addressed him as 'uncle'. Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré to the family in 1872 "“ and the young composer was soon captivated by Viardot's youngest daughter, Marianne.

Fauré courted Marianne for four painful years. Turgenev, to whom Marianne was particularly close, liked Fauré and helped to convince her to accept his proposal. But the timid Marianne was, it seems, scared by the intensity of Fauré's passion for her and a few months later, in autumn 1877, she broke off the engagement, leaving him heartbroken.

In 1875, while he was still hoping for Marianne's hand in marriage, Fauré had composed his first Violin Sonata Op. 13, dedicated to her violinist brother, Paul Viardot. The four-movement sonata follows a conventional format, but its ardent emotional world is more personal than anything Fauré had written before. The first movement, in sonata form, overflows with joie de vivre; the second movement features an unusual 'heartbeat' rhythm which Fauré used again in several different works (notably his Seventh Nocturne). The scherzo is gossamer-light and playful, and the finale, like the first movement, alternates a sweet-natured intimacy with a passionate élan that recalls the music of Schumann, of which Fauré was especially fond.

Thanks to Fauré's friends Camille and Marie Clerc, with whom he often spent summers in Normandy, the Sonata became his first published chamber work; Camille Clerc sent it to the German publishing firm Breitkopf & Härtel, who agreed to print it, though without paying the composer any royalties. Fauré himself played the piano at the work's premiere in January 1877, with the violinist Marie Tayau, to an ecstatic audience response. 'There is no stronger work among those which have appeared in France and Germany over the past several years,' wrote Saint-Saëns after hearing it, 'and there is none with more charm.'

Of Fauré's shorter works for violin and piano, the Berceuse Op.16 has always been the best loved. Its perfectionism, with no note extraneous to musical purpose, is characteristic of Fauré's finest compositions, and its magical, hushed atmosphere renders it rather more than a 'cradle song'. Written in 1878-9, it was the work that convinced the Paris music publisher Julien Hamelle to take Fauré on (again without royalties). According to Fauré's biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux, Fauré himself attached 'no importance' to the Berceuse; but its beauty has always made it irresistible to violinists and listeners alike.

The Romance Op.28 was written in 1877; the decorative style of its first theme "“ akin, perhaps, to the languid curlicues of Art Nouveau "“ contrasting with a more sweeping, incisive mood in the second section in G minor. Fauré wrote that its first performance at the Viardots' home in Bougival succeeded 'to the accompaniment of grinding teeth'. The Viardots disapproved of Fauré's working methods, notably that he wrote slowly ('You must take less trouble and get on with it!' Louis Viardot advised); also that he was writing chamber music and songs rather than opera, the only medium in which a composer could achieve fame and fortune in Paris at the time. Eventually Fauré came to understand that his break with Marianne might have been for the best; he told his younger son, Philippe, that 'in the dear surroundings of the Viardot home I would have been persuaded to alter my course'.

Fauré was already finding his most consistent success in his songs, three of which feature here in instrumental arrangements: their sinuous melodies, set over evocative piano parts, enable them to work almost as well on a violin or cello as a human voice. Sérénade toscane, which Fauré wrote in the aftermath of his broken engagement, is a sweet yet acid-tinged work steeped in the frustration of unrequited love. Its words are by the poet and singing teacher Romain Bussine, a close friend of Fauré's. So, too, are those of the contemporaneous Après un rêve, apparently 'after a Tuscan poem' "“ though their apposite and timely nature makes one wonder whether this is truly the case. The song describes with aching poignancy the disillusionment upon discovering that a passionate dream was merely an illusion.

Clair de lune, written some ten years later in 1887, demonstrates a new sophistication in Fauré's songs, resulting not least from his choice of poetry by Paul Verlaine: the great French Symbolist poet's polished, sensual language matched Fauré's music to perfection and Fauré's Verlaine settings are consistently among his most masterful songs. Clair de lune pictures a Watteau-esque scene of 18th-century courtly love. Its vocal line interweaves with a delicate counterpoint on the piano, perhaps mirroring moonlight in the waters of the fountain. Fauré orchestrated the song the following year and incorporated a voiceless version into his Suite Bergamasque in 1919.

Fileuse and Sicilienne are drawn from another orchestral suite: Fauré's incidental music to Pélléas et Mélisande, the Symbolist drama by Maurice Maeterlinck on which Claude Debussy based his operatic masterpiece. Fauré wrote most of the Pélléas incidental music in 1898 for a production in London featuring the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell "“ for which Debussy had refused point blank to adapt any of his own music. After seeing this production, Maeterlinck wrote to Mrs Campell declaring that it 'filled me with an emotion of beauty the most complete, the most harmonious, the sweetest that I have ever felt to this day.' Fileuse is a spinning song, a delicate melody over a rapid, murmuring accomp animent; the sombre, graceful Sicilienne actually had its origins in Fauré's incidental music for Le bourgeois gentilhomme, dating from 1893.

Fauré was never shy of recycling good musical material in this way. Following the success of his First Violin Sonata, he had embarked on a concerto for the instrument in 1879, but abandoned it unfinished "“ extended orchestral forms were never his favourite medium. It is likely that he originally composed the tranquil Andante Op.75 for the slow movement of the ill-fated concerto, reworking it for the Andante only in 1897. The opening movement of the concerto itself has since been resuscitated; it is intriguing to see that Fauré reused its main theme in his very last work, his String Quartet.

Fauré was appointed director of the Paris Conservatoire in 1905. During his long reign there "“ during which he was nicknamed variously 'The Archangel' and 'Robespierre' "“ he occasionally composed pieces for use in the institution's exams and competitions. One such was the Morceau de lecture a vue "“ literally, 'short piece for sight-reading'. Fauré's harmonic sleight-of-hand makes him a terrifying composer to sight-read at the best of times, but the engaging lyricism of these few pages are such that scared students might well forget their fright upon discovering it.

In 1920 Fauré was finally asked to retire as director of the Conservatoire "“ to his chagrin at first. Before long, however, he discovered that despite his poor health and severe deafness, he was now free to dedicate himself entirely to composition for the very first time. A tremendous flowering of late masterpieces ensued, among which the Piano Trio is perhaps first among equals. Throughout his life, Fauré had found it easiest to compose away from the stresses of life in Paris. He was particularly fond of peaceful waterside locations and in 1918 he discovered the beauties of Annecy-le-Vieux, where he rented a house for the summer several times. In September 1922 he wrote to his wife, Marie, from Annecy: 'An important section of the Trio was begun a month ago and is now finished. The trouble is that I can't work for long at a time.. My worst tribulation is perpetual fatigue.' He eventually completed the work the following February.

The Trio is rapt and autumnal in mood, its harmonic language "“ combining traditional tonality with modal inflections and enharmonic intricacies "“ strongly characteristic of Fauré's late style, as are its spare textures and reflective atmosphere. The first movement is lyrical and flowing, its melodic lines concentrated into statements etched as delicately yet strongly as a drawing by Matisse; the coda, blending the movement's two principal ideas, seems to contain echoes of distant bells that Fauré spoke of remembering, and incorporating almost unconsciously into his music, from his childhood in the countryside. The slow movement enters a tender, resigned world, the violin and cello exchanging long phrases over a steady, pulsing piano accompaniment "“ again with a deceptive simplicity that perhaps could only spring from a composer working at the sum total of his powers. The finale soars ahead, however, with Fauré's perennial élan, the stringed instruments in declamatory unison contrasting against upward cascades in the piano, building up to a positive, energetic conclusion. The trio was first performed on Fauré's 78th birthday at the Societé Nationale de Musique; sadly the composer was too ill to attend. 'If he lives to be a hundred, how far will he go?' his friends mused on hearing this astonishing work for the first time.

Fauré did not live to be a hundred; he died in November 1924 at the age of 79, leaving behind him one of France's most exquisite treasuries of chamber music and song. 'I did what I could,' he said to his sons on his deathbed. 'Now let God be my judge.'

For information about ![]() Gil Shaham recordings visit Public Radio MusicSource.

Gil Shaham recordings visit Public Radio MusicSource.

* reprinted from the CD booklet, used with permission.