The Second Circle:

Love Songs of Francesco Landini

By Susan Hellauer, of Anonymous 4

November, 2001

|

||

|

This way I went, descending from the first

Into the second circle... —Dante, Inferno, Canto V 1

The 14th century was a time of religious and social upheaval in western Europe—constant war, the exile of the papacy in Avignon, and of course the Black Death. Italy suffered no less than any other land, but amidst the unrest and terror she produced a constellation of literary stars that outshone all of Europe at that time.

This was the trecento, or "three hundreds," as the Italians call the 14th century. It was the time of Dante, Petrarca, and Boccaccio, and of a new lyrical way of writing poetry (the heritage of the Provençal troubadours) called by Dante the dolce stil nuovo or "sweet new style." The subject was love and desire—exalted by Dante the young lover in the Vita Nuova (1292-94), and transcended by the mature poet in the Divine Comedy, where lustful lovers were tossed and blown about in the second circle of hell. At the same time, a sweet new style of musical composition came into being, almost without precedent: a wave of talented composers produced polyphonic songs based on lyrics either playful or romantic, comical or serious, but always highly personal in expression.

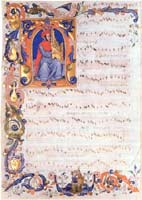

It is our great loss that no examples survive of the trecento art of setting poetry (of Dante and Petrarca, among others) to musical recitation. But we are fortunate that about 600 musical works have come down to us, preserved in a number of fine manuscripts. Almost all of these works are secular—there are only a small handful of sacred polyphonic pieces—and although the most frequent theme is that of courtly love, some texts deal with the natural world or the supernatural world of classical deities. There is even an occasional moral sermon.

In Boccaccio's Decameron (1355), each day's storytelling ends with the singing of a ballata, which in its earliest form was a simple call-and-response dance tune. By the latter half of the century, composers began to favor the ballata over the nearly forgotten madrigal (an ornate duo or trio on a fanciful text) and the caccia (a canonic song on a lively outdoor theme), and it became artfully stylized. The structure of the ballata's stanza is most easily shown by a scheme where the letters A (a) and b represent the two alternating musical sections:

| A | ripresa | verse 1 (refrain) |

| b | piede | verse 2 |

| b | piede | verse 3 |

| a | volta | verse 4 |

| A | ripresa | verse 1 (refrain) |

|

||

|

In the early trecento, ballate were composed as unaccompanied melodies; later, composers set them in great numbers for two and three voices. Our program onsists of several ballate of Francesco Landini, in whose hands they became creations of subtle refinement and emotional revelation, with a harmonic richness unknown before in Italian music.

A prolific composer and virtuoso organist who attained near-mythic status in his day, Francesco Landini (born c. 1335) was fortunate in his home town, for literature and the arts in Florence were amply supported by a wealthy and cosmopolitan merchant-nobility. As a child, Francesco was left blind by smallpox, but he mastered singing and several instruments, eventually becoming chief musician at the church of San Lorenzo. An early "renaissance man," Francesco (whose surname was not used in contemporary manuscripts) was counted among the neo-humanistic intellectual elite of Florence. He was an honored port as well, and certainly wrote some, if not most, of his own song texts. His expressive powers were legendary, as witnessed by a contemporary account of a day amongst the leisured classes:

...the sun was coming up and beginning to get warm; a thousand birds were singing. Francesco was ordered to play on his organetto to see if the singing of the birds would lessen or increase with his playing. As soon as he began to play, many birds at first became silent, then they redoubled their singing and, strange to say, one nightingale came and perched on a branch over his head.

—Giovanni de Prato, Il Paradiso degli Alberti (1389) 2

Nearly a quarter of the entire surviving trecento repertory, 154 works, are by Francesco, and of these, 140 are ballate in two or three voices. Almost all their texts are intensely personal meditations on topics of courtly love, or courtly lust: desire, hope, rejection, misery. Their musical style is a combination of the Italian melodic grace that characterized the first generation of trecento composers, including Francesco's younger self, and elements of contemporary French songwriting: complex harmonies, a strong tonal center, and regular meter, to name the most notable. This influence from abroad is not surprising, since Florentine merchants, clerics and scholars had strong ties to their French counterparts. Francesco and his fellow composers also began to borrow French notational methods, verto (open) and chiuso (closed) endings (what we call first and second endings), and showed a preference for three-voice writing, including the very French "accompanied song" texture, where one voice part, the superius, clearly takes on a solo role. The result of this marriage of Italian and French taste and technique in the ballata was a richly nuanced hybrid capable of a wide range of expression.

Scholars have attempted to "chronologize" Francesco's works, based in part on some scant biographical references, but mainly on the increasing French influences. Thus the two-voice ballate are in general probably older than the three-voice works, and those that show remnants of dance rhythms (Echo la primavera, Angelica biltà, La bionda treĉĉa) may be earlier than duos with a more emotionally sophisticated response to the text (e.g. Ochi dolente mie, Nella partita).

Three-voice songs with the most Italian and the fewest French characteristics, and with all three parts texted (Cara mie donna, Muort' oramai) are probably earlier than those with two parts texted in the original sources (Che chos' è quest'amor, Gran piant' agli ochi).

Three-voice songs with a single texted part and "instrumental"-sounding accompanying voices (e.g. Non ara ma' pieta) are considered most French-influenced, and might represent the latest stage of Francesco's compositions. The careful listener will hear that we occasionally add text to an untexted line—as was also done in Francesco's time. In spite of the foregoing analysis and classification, the fact is that a ballata by Francesco, whether early or late, simple or complex, in two voices or three, is unmistakably his and no other's. And the miracle is that within each ballata Francesco creates a unique musical and emotional world, consistently transcending the formulaic structure, with the music perfectly matched to the mood of the text.

Francesco died at Florence in 1397 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo, where he served for over 30 years. In the 15th century his tombstone was removed and "recycled"—to be found again in the mid-19th century in the convent chapel of San Domenico at Prato. It was returned to San Lorenzo in 1890, where it is now. His epitaph reads:

Luminibus captus Franciscus menti capaci

Cantibus organicis, quem cunctis Musica solum

Pretulit, hic cineres, animam super astra reliquit.

(Francesco, deprived of sight, but with a mind skilled in instrumental music, whom alone Music has set above all others, has left his ashes here, his soul above the stars.) 3

| (1) Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Vol. 1: Inferno, trans, Mark Musa, The Penguin Classics, 1984, p. 109, lines 1-2. |

| (2) Quoted by L. Ellinwood in New Oxford History of Music vol. III, p. 36 |

| (3) Quoted and trans. L. Ellinwood, op. cit. p. 79 |

| Reprinted by kind permission of Susan Hellauer |

| from the liner notes to Anonymous 4's CD |

| The Second Circle: Love Songs of Francesco Landini |

| (Harmonia Mundi 907269, © 2001) |